Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a condition caused by an underactive thyroid gland, resulting in insufficient production of thyroid hormones. Hyperthyroidism, on the other hand, is a condition caused by an overactive thyroid gland, resulting in an excess production of thyroid hormones.

Although hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are different diseases and have different symptoms, both are diagnosed by measuring thyroid hormone levels in the blood, specifically TSH and free T4.

In this article, we’ll explain the thyroid hormones and how to interpret their levels in blood tests.

How Does the Thyroid Gland Work?

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the base of the neck. It captures iodine consumed in food and combines it with an amino acid called tyrosine to synthesize two hormones known as triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4).

The T3 and T4 synthesized by the thyroid are released into the bloodstream, where they act on all the cells of our body, regulating their metabolism, dictating how cells transform oxygen, glucose, and calories into energy.

- When the thyroid produces too much T3 and T4, our metabolism speeds up.

- When the thyroid produces too little T3 and T4, our metabolism slows down.

Generally, of the total hormones produced by the thyroid, 80% are T4 and 20% are T3. Although produced in smaller quantities, T3 is a much more potent hormone than T4, with its blood concentration directly dictating the body’s metabolic rate.

T4 is actually a prohormone, meaning it is a precursor to T3. 80% of the T4 released into the bloodstream, when reaching organs or tissues such as the liver, kidneys, spleen, muscles, or fat, is converted into T3 to be utilized by the cells.

Therefore, T3 is the thyroid hormone that effectively acts in our body, originating predominantly from circulating T4. Only a tiny portion of the active T3 is directly produced by the thyroid.

What is Free T4?

Over 99% of circulating T4 and T3 are bound to a protein called thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG).

These TBG-bound hormones are inert and cannot be used by organs and tissues. Therefore, only a tiny fraction, called free T4 and free T3, are chemically active and can modulate the body’s metabolism. Only free T4 can be transformed into T3 in organs and tissues.

In summary:

- The T3 hormone is the one that effectively acts on body cells, modulating metabolism.

- Most of the active T3 is derived from the conversion of T4 in peripheral tissues.

- Since more than 99% of T4 is bound to TBG, only a tiny fraction of free T4, less than 1%, provides T3 for the body’s organs and tissues to use in their cells.

In conclusion, measuring free T4 in the blood is the test that really gives us an idea of how much potentially viable thyroid hormone is in the circulation. If there is too much circulating free T4, there will be too much T3 production in the organs, leading to hyperthyroidism. If there is too little circulating free T4, there will be a lack of T3 in the tissues, resulting in hypothyroidism.

In clinical practice, the measurement of free T4 is more valuable than the measurement of T3 or free T3 in most cases.

What is the Role of TSH?

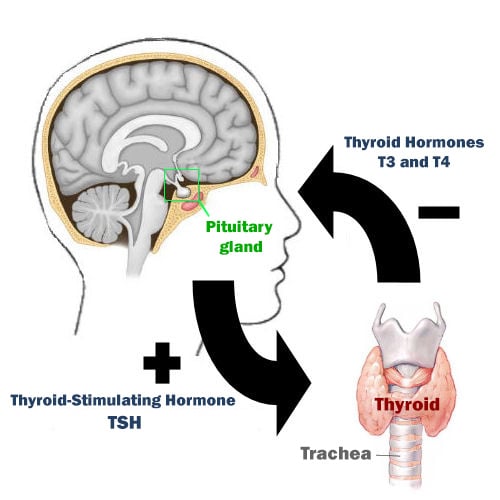

The amount of T3 and T4 produced by the thyroid gland is carefully regulated by the central nervous system, specifically the pituitary gland, located at the base of the brain.

In people with a healthy thyroid gland, the amount of free thyroid hormone in the blood is kept at a level that is neither too high nor too low. When there is too much free T4 in the blood, the thyroid gland reduces its production of T3 and T4. On the other hand, if there are signs that free T4 levels are becoming insufficient, the thyroid gland quickly begins producing more T3 and T4 to keep the body’s metabolism from slowing down.

The signal for the thyroid to increase or decrease its production of T3 and T4 comes from the pituitary gland, via a hormone called thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).

See the figure above and follow the reasoning. When circulating levels of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) are low, the pituitary gland detects this shortage and responds by increasing the secretion of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). This elevation in TSH signals the thyroid gland to enhance the production of T3 and T4.

As the concentrations of T3 and T4 rise to optimal levels, the pituitary gland recognizes this equilibrium and correspondingly decreases TSH production. This reduction in TSH lessens the stimulation of the thyroid gland, thereby preventing the overproduction of thyroid hormones.

The interplay between TSH and free T4 levels is a finely tuned mechanism. The pituitary gland continually adjusts TSH concentrations to maintain a delicate balance. It ensures sufficient thyroid hormone production to meet the body’s needs while avoiding excessive stimulation of the thyroid gland.

What are the Normal Values of TSH and Free T4?

In most cases, the TSH and free T4 measurements are enough to assess the functioning of the thyroid.

Before we explain how to interpret the results of these two hormones, we need to know their reference values (these values can vary slightly from one laboratory to another).

- Normal TSH values: 0.4 to 4.5 mU/L (some centers accept up to 5.0 mU/L as an upper value).

- Normal free T4 values: 0.7 to 1.8 ng/dl.

Note: A study by the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry suggested that the normal range for a healthy thyroid should be up to 2.5 mU/L. This is because they found that 95% of the healthy people they tested had thyroid levels (TSH levels) between 0.4 and 2.5 mU/L. However, another study from Germany, which also carefully selected participants, found the normal range to be slightly wider, from 0.3 to 3.63 mU/L. If we start using 2.5 mU/L as the upper normal limit for TSH, it means that many more people could be diagnosed with a mild form of low thyroid function, known as subclinical hypothyroidism. However, no clear evidence exists that TSH levels between 2.5 and 5.0 mU/L are harmful. So it’s debatable whether we should label people with these levels as having a thyroid problem.

The latest method for measuring TSH is known as the Third-generation TSH chemiluminometric assays. This advanced technique is more sensitive than earlier versions, allowing it to detect very low TSH levels, down to 0.01 mU/L. This improvement means it can identify even the smallest changes in TSH levels in the body.

What Does It Mean to Have an Elevated TSH Level?

TSH levels rise whenever the pituitary gland senses a drop in circulating thyroid hormone levels.

In patients with hypothyroidism, the pituitary needs to maintain higher than normal TSH levels (above 4.5 or 5 mU/L) to constantly stimulate the thyroid to increase its production of T3 and T4.

Different Scenarios of High TSH:

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

If the thyroid disease is still mild and the elevation of TSH can stimulate the production of thyroid hormones to keep them at adequate levels, the patient will not show any symptoms, as the symptoms of hypothyroidism only appear when free T4 levels are low. This is the case of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is an early form of hypothyroidism (suggested reading: Subclinical Hypothyroidism).

Overt hypothyroidism

If the thyroid disease is severe, no matter how much the pituitary increases TSH production, the patient’s thyroid will be unable to respond by producing more thyroid hormones to normalize blood levels.

In these cases, the patient has elevated TSH, generally above 10.0 mU/L, and low levels of free T4. As their free T4 is low, the patient usually has the typical symptoms of hypothyroidism.

Patients with untreated hypothyroidism can have very high levels of TSH, sometimes above 100.0 mU/L.

Central Hyperthyroidism

This condition occurs when TSH and free T4 levels are both elevated.

The issue in this scenario is with the pituitary, not the thyroid. The pituitary produces too much TSH despite already high levels of thyroid hormones in the blood, leading to symptoms of hyperthyroidism. This pituitary-driven hyperthyroidism is less common than thyroid-related hyperthyroidism.

In Summary, What Could a High TSH Level Indicate?

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism: Mild thyroid disorder with slightly elevated TSH (5.0-10.0 mU/L) but normal thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), presenting no symptoms.

- Clinical Hypothyroidism: Advanced thyroid disease with very high TSH (often above 10 mU/L) and low T4 levels, leading to typical hypothyroidism symptoms.

- Central Hyperthyroidism: Uncommon condition where both TSH and T4 are high, caused by pituitary dysfunction, resulting in hyperthyroidism symptoms.

What Does It Mean to Have a Low TSH Level?

The logic applied to low TSH is the same as that for high TSH. If there is an abundance of thyroid hormone circulating in the blood, the pituitary gland responds by decreasing its release of TSH, thereby reducing the stimulation of the thyroid.

Similarly, there are three distinct situations that can occur when TSH levels are low:

Subclinical Hyperthyroidism

In cases where the thyroid is overactive, TSH levels plummet to halt further stimulation of the gland. In subclinical hyperthyroidism, TSH is typically below 0.4 mU/L, but free T4 levels remain normal. This occurs because the gland is highly responsive, and minimal amounts of TSH are enough for the thyroid to produce hormones. Therefore, patients usually do not show symptoms at this stage.

Overt Hyperthyroidism

Certain conditions can cause the thyroid to become excessively active and operate independently of the pituitary gland, producing hormones even without TSH stimulation.

When there’s a high level of free T4 in the bloodstream, the pituitary is essentially “inhibited”, producing almost no TSH, with blood levels below 0.1 mU/L. The patient therefore has very low levels of TSH, but high levels of free T4, resulting in overt hyperthyroidism.

Central Hypothyroidism

When both TSH and free T4 levels are low, it suggests a normally functioning thyroid that is adequately responding to reduced TSH levels.

The problem primarily resides in the pituitary gland. Despite low free T4 levels, the pituitary fails to sufficiently elevate TSH secretion to stimulate the thyroid into producing additional hormones, thus safeguarding the patient from developing hypothyroidism.

This type of hypothyroidism, stemming from the pituitary gland, is less common compared to hypothyroidism that originates directly from the thyroid.

In Summary, What Could a low TSH Level Indicate?

- Subclinical Hyperthyroidism: overactive thyroid, leading to TSH levels falling below 0.4 mU/L to minimize gland stimulation, while free T4 levels remain normal. Patients usually don’t exhibit symptoms.

- Overt Hyperthyroidism: the thyroid gland becomes excessively active and functions independently of the pituitary gland. This results in a high concentration of free T4 and extremely low TSH levels (below 0.1 mU/L), leading to obvious symptoms of hyperthyroidism due to the elevated free T4.

- Central Hypothyroidism: both TSH and free T4 levels are low, indicating a normally functioning thyroid that’s responding appropriately to reduced TSH. The underlying issue is with the pituitary gland, which fails to increase TSH production in response to low T4.

References

- Laboratory assessment of thyroid function – UpToDate.

- Thyroid Function Tests – American Thyroid Association.

- Assessment of Thyroid Function: Towards an Integrated Laboratory – Clinical Approach – The Clinical biochemist. Reviews.

- American Thyroid Association guidelines for use of laboratory tests in thyroid disorders – JAMA.

Author(s)

Médico graduado pela Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), com títulos de especialista em Medicina Interna e Nefrologia pela Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Sociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia (SBN), Universidade do Porto e pelo Colégio de Especialidade de Nefrologia de Portugal.